INTRODUCTION

The global healthcare scenario indicates the disability prevalence rates of both intellectual and physical disabilities among the populace of different countries (Gosadi, 2019). The contemporary data indicate that, over the time, the disability prevalence rates have been managed at a controlled level by certain healthcare, social, educational, economic, and medical measures (Gosadi, 2019; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). If the situation of Saudi Arabia is specially taken into account, the estimates according to the World Health Organization (WHO) show that the prevalence of disability in Saudi Arabia is estimated to be around 2.7% in 2016, which is lower than the global average (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). However, the actual numbers may vary as the definition of disability and methods of data collection may differ across Saudi and other countries (Gosadi, 2019). The lower disability rate is an indication that certain measures are carried out by the government and private agencies in coordination with healthcare providers to maintain a controlled prevalence of disabilities (Gosadi, 2019).

In general, disabilities in Saudi Arabia are caused by various factors such as genetic disorders, congenital malformations, accidents, chronic diseases, social inequalities, economic constraints, family reasons, personal mental disabilities, and various other reasons (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Gosadi, 2019; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). The Saudi Arabian government has implemented policies and programs to improve the quality of life of people with disabilities, including education, healthcare, and employment opportunities (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). The focus of these programs and policies is on some important aspects, including appropriate intellectual and physical strategies, plans and programs, policy formulations and legal regulations in organizations, funding programs for the disabled, service programs to detect and treat the prevalence of disabilities, a reliable supply of medication and rehabilitation services, and systematic measures to train the affected population and healthcare providers, as well as educational institutions, policy makers, officials, etc. from related fields (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Alharbi et al., 2020). In addition, the measures also include regulations for information communication technology (ICT) systems and the use of artificial intelligence to enable the planning, monitoring, and evaluation of such programs that serve to regulate disabilities in the population (Mavrou et al., 2017; Barlott et al. 2020). In addition, the Saudi government is also taking measures to develop some social armaments that promote community participation and income-support programs for people with disabilities of all kinds, along with efforts to maintain the political, social, cultural, and economic environment for the right policies (Ferreras et al., 2017; Muzafar and Jhanjhi, 2020; Medina-García et al., 2021).

This paper discusses some of the experience and background to health management and disability schemes in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) to date, including brief demographic information from official sources. Some aspects of change in the present are also discussed. In addition, the current scenario is discussed in conjunction with future implications based on past experience. Finally, some data are provided on future recommendations and suggestions for a socially sustainable environment with lower disability rates in Saudi Arabia. The purpose of this paper is to examine the past scenario and the changes that have led to better management of disability prevalence in Saudi Arabia. It also attempts to examine various dimensions of the current need for disability management through interlinked efforts of the health sector and other relevant sectors. Some aspects of social needs such as a better education system and addressing domestic concerns will also be part of the literature to identify the reasons and ways out of disability in Saudi Arabia. In addition, some ways of improvement and proper research analysis will be discussed to provide a better future-oriented outcome for the coming generations. The aim is to present the latest evidence and social analysis on the prevalence of disability in Saudi Arabia to help readers understand the need to focus on the right, comprehensive, and timely interventions in this area. This paper will also help the policy makers and the ministries in Saudi Arabia to develop a proper strategy and planning/policy for better management of disability in the future. Finally, the data will also help readers worldwide to develop a sense of the problem and the need to take forward-looking steps for better inclusion of persons with disabilities in the community as early as possible.

METHODOLOGY

In this review study, a methodological and descriptive approach was chosen to collect only the most recent and relevant data from the last 5 years (2018-2023). To this end, a quick search was conducted with various search terms such as disabilities rates in KSA, disability measures, past and current analyses, supportive technologies, disability technologies, and social analyses of disabilities in KSA. Relevant data were collected from publications found on Google Scholar, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus platforms, among others. In addition, only English-language literature was included in this review study to enable a global understanding. It is important to note that this study is not financially supported and does not involve a clinical trial that may require ethical approval or informed consent.

The studies included are mostly from the last 5 years and have deepened the analysis of the social impact of disability in different areas of education, healthcare, administration, and other professions. The search terms were limited to the previously developed keywords, and the selected articles included peer-reviewed journals, reviews, research studies, short letters to the editor, and journals dealing with socioeconomic and educational perspectives related to people with disabilities. In addition, data that did not include details of articles, dissertations, theses, books, technical reports, or conference proceedings were avoided due to lack of accessibility and comprehensibility.

RESULTS

Healthcare in Saudi Arabia

The healthcare development scenario in KSA has not fundamentally changed, but it has taken years to evolve into a state-of-the-art system capable of addressing multiple healthcare challenges (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). In the past, until the mid-1990s, there were no rehabilitation centers and hospitals in KSA, and in the 1800s, there were only two such hospitals for a population of eight million people (Al-Hanawi et al., 2019; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). Furthermore, there was virtually no research in this area. With time, such topics were included in the curriculum of universities, which taught some aspects of psychiatric health related to traveling during Umrah and Hajj (Yeganeh, 2019; Rahman, 2020). In addition, psychiatric research, legal and ethical issues, especially human rights issues related to mental healthcare, issues related to the patient–physician relationship, the right to treatment, and consideration of insanity in criminal cases, such as probationers, were not considered to the extent deemed necessary today (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). In the late 1980s, some educated professionals began to propose changes in mental health institutions regarding appropriate patient care, consideration of the human rights of persons with disabilities, psychotherapy, biopsychosocial treatment, and cultural adjustment programs at the academic and professional levels (Gorski, 2005; Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Noor, 2019; Session, 2019).

Over time, professionals and the general public began to make the connection between Islamic and cultural values and scientific advancement to understand the need for timely action for equitable healthcare outcomes rather than relying on the belief system alone (Gorski, 2005; Al Eid et al., 2020). This trend of relying on a strict religious belief system for healing and ignoring practical measures is still prevalent in some rural areas of KSA (Al Eid et al., 2020). Psychic flogging or cauterization is a trick used to cure people suffering from mental or physical disabilities from such evils according to the ancient belief systems (Al Eid et al., 2020; Al-Subaie et al., 2020). Modern science assumes that these tricks aggravate diseases and mental disabilities and hinder healing. However, in urban settlements, the thinking has changed and now practical measures such as medical prescription and psychotherapy are favored for such mental or physical disabilities (Al-Subaie et al. 2020; Alsufyani et al., 2020).

This urban–rural divide and western–eastern cultural blending also affect the mental and physical conditions of people, leading to physical and psychiatric disorders in the KSA population (Muzafar and Jhanjhi, 2020; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). The restricted society forces women in particular to seek more psychiatric help compared to men. Similarly, the legal scenario also influenced the mental health status in KSA, where in the late 1990s, discharge of people with mental disabilities after some time often resulted in re-admission of patients along with their supervising psychiatrist if the person had assaulted someone (Alshahrani et al., 2019; Al Asmri et al., 2020). Due to this prevalent scenario, healthcare professionals and security agencies intensified their defensive treatment style and prolonged detention times, resulting in prematurely overcrowded psychiatric hospitals and prisons and an increasing number of chronically disabled people (Tyrovolas et al., 2020). Similarly, academic forums and training opportunities in psychiatry and physical rehabilitation have been lacking in recent years, initiating a slow systemic change in countries focused on mental health management (Alshahrani et al., 2019; Tawfik et al., 2022). In addition, drug treatments were provided without specific guidelines until the late 1990s, when some thinking and action in this area developed (Tawfik et al., 2022).

The present scenario of disability management

The health delivery scenario in KSA has changed over the last two decades, with the past weakened mental health system playing an important role in systemic improvements and reforms (Berzin et al., 2015; Lussier-Desrochers et al., 2017). The available information on special populations affected by mental disabilities is explored as causes for the positive development of the healthcare system in KSA (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). Previous studies indicate the prevalence of depression in the population, with women, rural dwellers, divorced and widowed, unemployed, elderly, and people in freedom having higher rates (Alanezi, 2021). Similarly, data have been collected over time on different age groups and people from different backgrounds to provide comparative analyses of the prevalence of certain psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, fear, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder (Noor, 2019; Alanezi, 2021). These studies have shown that there remains a high rate of undetermined, undiagnosed, and untreated psychiatric and physically disabled patients in KSA who require primary healthcare to accommodate these disabled individuals in the community (Rahman and Alsharqi, 2019; Al Asmri et al., 2020).

In Saudi Arabia, several surveys are currently being conducted to study the prevalence rates of disability in Saudi Arabia, such as the Saudi National Mental Health Survey (SNMHS), in which hospitals, disability centers, universities and research centers, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) collaborate to bring together researchers and clinicians not only at the national level but also at the international level (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Tyrovolas et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). The surveys conducted by the SNMHS and other such organizations aim to collect data on disability, rebalance rates, risk factors, comorbidities, treatment options, and international collaboration in health management (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Altwaijri et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). Reports from this body indicate that the types of disorders and characteristics of people with disabilities in the general population have evolved over time (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Alsufyani et al., 2020). However, this amount of information available on mental disorders in the general population of KSA is still small. However, these surveys have helped health ministries to develop strategies and management programs to address the increasing cases of disability in KSA. These studies help researchers to develop a sense of the prevalence rates of psychiatric and physical disabilities in the KSA population and the need for further appropriate health services (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Gosadi, 2019; Al-Subaie et al., 2020).

Need for advancement in disability handling

As already mentioned, the health system in KSA has changed drastically over time. The establishment of primary healthcare centers (PHCs) across KSA is one of the positive developments to combat disability in the population (Alnahdi, 2020; Toquero, 2020). This development has also been promoted and recognized by the WHO (Al Asmri et al., 2020). Different levels of care have been introduced in PHCs, including primary care units, general hospitals, and teaching hospitals, and these interventions have contributed to the improvement of disability-friendly healthcare for the population in KSA (Yeganeh, 2019; Al Asmri et al., 2020). Similarly, private healthcare facilities offer patients the opportunity to seek help for a fee. Patients can now also seek psychiatric counseling directly without prior referral (Al-Hanawi et al., 2019; AlAteeq et al., 2020). Currently, there are a large number of such private hospitals and psychiatric clinics in KSA that help people with mental disabilities and make them part of the healthy KSA society after appropriate treatment (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). Treatment options include psychotherapy, treatment with psychotropic drugs, addiction treatment, speech therapy, and rehabilitation services for the general and criminal populations (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021).

The country is now practicing an appropriate national mental health policy to recognize special programs for specific psychiatric problems in medical institutions. The establishment of the Saudi Arabian Mental and Social Health Atlas (SAMHA) in 2007 was a positive development in this regard, which helped to systematically address the mental health needs of the population by working on the 4-year follow-up studies (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Al-Subaie et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). These interventions helped to develop and improve the quality of care, expand health services, increase the number of healthcare providers and professional counseling, and link education and training programs on disability issues with the practical work of clinics. The measures include improving health infrastructure (more psychiatric beds and improved procedure manuals), providing inpatient and outpatient services, increasing budgets, establishing quality indicators, and improving social integration under the 2012 Mental Health Act (MHA) policies and procedures controlled by the MOH. Despite all these measures, the country still does not have a comprehensive community mental health system that could empower communities to improve healthcare (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Al-Subaie et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021).

Ongoing efforts and barriers to overcome hurdled healthcare development

Efforts are being made to improve the quality of medical education at the academic level, the training of psychologists at the professional level, and the training of professionals to recognize and solve problems with emotional, psychiatric, and physical disabilities (Fong, 2009; Alfredsson Ågren et al., 2020; Hoq, 2020). In addition, work is being done to improve counseling services in public and private institutions, and pharmacists and researchers are being trained and encouraged to monitor cases of disability (Sheikh et al., 2019). Disability prevalence detection rates need to be improved in order to implement a more comprehensive system of health management in KSA (Alshahrani et al., 2019). Professionals should be well-trained to recognize and differentiate psychiatric problems from medical and physical symptoms to enable appropriate disease management and treatment recommendations (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Rahman, 2020). Moreover, there is a need for the general population to become aware of the practical understanding and care needs of the disease, rather than relying solely on faith healing and traditional thinking processes, which are a major barrier to presenting, documenting, managing, and treating psychiatric and physical impairments in medical settings (Rahman, 2020; Chowdhury et al., 2021; Park, 2022).

Need for expansion of disability health services

Over time, more and more psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and especially faculties of disability management are being opened in KSA (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Kolotouchkina et al., 2022; Longoria et al., 2022; Park, 2022). The number of psychiatrists has also increased over time. The number of staff in the fields of psychology, psychiatric nursing, and psychiatric social work is also increasing rapidly (Gosadi, 2019; Alluhidan et al., 2020). In parallel, several graduate and postgraduate courses and training as well as medical degree subjects related to disability management and rehabilitation are being offered at various national universities (Chadwick et al., 2022; Kolotouchkina et al., 2022; Vouglanis and Driga, 2023).

Apart from the public educational and professional levels, inclusion of persons with disabilities is also increasing in the local population, in the form of greater acceptance and a family framework for the care of patients with disabilities (Gosadi, 2019; Vouglanis and Driga, 2023). As family care is considered a duty in KSA, care for these people begins at home in the extended and nuclear family (Harness, 2016; Borgström et al., 2019). However, the social stigma attached to mental and physical disabilities and their rejection in society are still present to some extent, just as in other countries around the world (Rueda and Cerero, 2019; Egard and Hansson, 2021). People try to associate such disabilities with evil spirits, evil eyes, magic, natural punishments, addictive behavior, or suicide attempts. The fact that such problems are not discussed and clarified with family members or the lack of trust in medical and health professionals are also barriers to coping with disability problems (Rueda and Cerero, 2019; Al Eid et al., 2020). Therefore, these issues need to be addressed through proper awareness among the masses by reminding them of the firm belief that Islam also calls for taking care of special people—values that have slowly faded into the background in western-oriented society (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Alsufyani et al. 2020; Muzafar and Jhanjhi, 2020).

Provision of services for special populations

People with disabilities require specialized health services. These services are needed for a range of groups, from school-age children who suffer from psychiatric illnesses and experiencing anxiety, grief, and depression, to older people who suffer from certain types of physical and health disabilities (Session, 2019; Yu, 2019; Alnahdi, 2020). Although special departments for disability and psychiatry have been established throughout KSA, there is still a lack of documentation and research to analyze this population in detail (Alotaibi et al., 2022). The main reason for the limited research is the symptomatology of reading and spelling difficulties, such as children suffering from hyperactivity, poor school performance, skipped classes, runaway, delayed milestones, concentration problems, impulsivity, mental disability, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, mood swings, toileting problems, and psychosis, to name a few (Osman and Diah, 2017; Khasawneh and Alkhawaldeh, 2020). Most adults suffer from anxiety and depression, so it is appropriate to look at studies of disability in the adult population of KSA. In these cases, medication, psychotherapy, and psychiatric analysis prove to be stable solutions as predicted by research studies (Alotaibi et al., 2022; Safari et al., 2023). However, this limited amount of data is not sufficient to resolve the prevalent rates of disability in KSA, and more comprehensive research and resources for detection, treatment, and outcome management are needed to regulate the problem (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022).

Cultural and religious influences and the need to integrate disability

As mentioned earlier, the strict practice of religion and the fusion of three cultures, namely Islamic culture, kinship culture, and Bedouin culture, have made the roots of KSA weak for the adoption of anything new. However, it is necessary to reaffirm the teachings of Islam to dictate the ethical and moral social norms that guide the treatment of people with some type of disorder. Since mental health is highly dependent on emotional, cultural, religious, and personal reasons, these concerns must be considered when treating people with mental disabilities (Nair, 2019; Yeganeh, 2019; AlAteeq et al., 2020; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021).

The Saudi healthcare system today

Recently, the WHO (2018) reported on the scenario of mental healthcare in KSA by estimating certain facts and figures. The estimated number of mental health professionals is 19.4 per 1 million population in 2018 which is much higher than the global average of 6.6 per 1 million in low-income countries and much lower than that in high-income countries, which is 64.3 per 1 million. The number of psychiatrists is also quite low (7%), compared to the global average of 20% (Noor, 2019; Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Sarasola Sanchez-Serrano et al., 2020). In addition, estimates of mental health spending show that the KSA government’s total spending is 78% higher than the proportion of budget allocations in low-income countries (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Al Ammari et al., 2021). The number of beds for psychiatric patients is also lower, at 18.4 per 1 million, than the 52.6 million in high-income countries (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; BinDhim et al., 2021). Similarly, several comparative analyses are now regularly conducted to map the current situation of mental healthcare and disability services in KSA in international collaboration, which is helpful in setting long-term strategies and managing healthcare (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Alanezi, 2021).

It is important not to rely solely on these estimates, as they may be misleading with regard to the prisoners in the data collection and the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may vary depending on the research study. In particular, the WHO has recommended integrating mental healthcare into primary care facilities to ensure better access, reduce prevalence of disability and social stigmatization of patients and their families, and improve overall health facilities and capacity to treat mental health problems (Noor, 2019; Rahman and Alsharqi, 2019; Alanezi, 2021). This aspect is implemented through the provision of primary care physicians, postgraduates, counselors, doctors, and social workers in conjunction with the medical field (Rahman and Alsharqi, 2019; Al Asmri et al., 2020).

In addition to the KSA’s 2030 policy vision, the MOH is also developing new dimensions of the healthcare system to help people acquire a patient-centered medical care model for better social, mental, and physical health management (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Al Asmri et al., 2020; Alharbi et al., 2021; Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). This system encompasses various dimensions of healthcare, such as chronic care, emergency care, planned care, safe birth, and the final stage of disease management (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019). These services cater for both mentally and physically disabled people in KSA. There is a likelihood of intersectoral collaboration between the various stakeholders in the KSA health sector to ensure racial transformation of disability management and genuine community acceptance (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Chowdhury et al., 2021). This strategy aims to close the existing gap in disability care in order to provide quality services in the future.

Some reasons for disability

The problem of substance abuse

The problem of alcohol or illegal drug consumption is somewhat limited in KSA due to the strict prohibition in religion and the cultural implementation (Tawfik et al., 2022). Furthermore, strict legal rules and regulations prevent such activities. Nevertheless, alcohol consumption per person in KSA is quite low compared to that in other Middle Eastern countries (Altwaijri et al., 2020; Tawfik et al., 2022). Regarding substance abuse, the available data for a detailed estimate are limited. However, there are some data on tobacco use in various forms suggesting that the rates are still low compared to those of other countries (Tawfik et al., 2022). This makes substance abuse a less common cause of disability of any kind, depending on how many alcohol-dependent individuals are receiving psychiatric treatment or have been admitted to psychiatric hospitals and substance abuse treatment centers (Alluhidan et al., 2020; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Tawfik et al., 2022).

However, as substance abuse continues to evolve, so do trends in the types of drugs, consumption patterns, and accessibility to the general public. Therefore, more detailed research on this topic is required to gain insights into the issue of disability (Osman and Diah, 2017; Alluhidan et al., 2020).

Some researchers have pointed out that psychiatric problems also occur as a result of some disabilities in people that make them vulnerable to mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric problems (Ferreras et al., 2017; Osman and Diah, 2017; Alluhidan et al., 2020; Altwaijri et al., 2020). In such cases, psychiatric counseling is recommended in order to bring the patient’s health condition under control. However, research shows that even this psychological counseling strategy has limited impact on patient outcomes. In this country, the majority of the population believes that medications (psychotropic drugs) are safe for patients (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Al Ammari et al., 2021; BinDhim et al., 2021).

Limited suicidality rates

As with substance abuse, the available data on suicidality appear to be unconfirmed due to the limited research on this topic. A study conducted in the last decade found that the suicide rate in the Saudi population is lower than that among non-Saudi populations. Data provided by the WHO in 2018 also estimated the suicide rate to be only 3.4 per 1 million population per year, which is quite low compared to the average global suicide rate of 10.5 per 1 million (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Altwaijri et al., 2020). This suggests that suicidality is only a minor contributor to disability prevalence and that mental health disorders cannot be identified simply from data on suicidality (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Al Ammari et al., 2021; BinDhim et al., 2021).

Domestic violence and dementia and its impact on caregivers

Dementia affects hundreds of thousands of adults in KSA and has an indirect impact on the health of caregivers. Caregivers, in turn, can suffer adverse physical, mental, and financial limitations (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Al Eid et al., 2020; Al Ammari et al., 2021). Most of them affected are women, as they mostly stay at home and take care of the family and therefore suffer from a wide range of emotional disturbances, depersonalization, and anger problems (AlHadi and Alhuwaydi, 2021). Moreover, elder abuse in the form of neglect, psychological abuse, financial exploitation, exploitation of family rights, and abandonment also increases the likelihood of mental disability in the masses, which in extreme cases leads to morbidity and mortality and is one of the major reasons for the prevalence of disability in the society (Ee Wong, 2012; Noor, 2019; AlHadi and Alhuwaydi, 2021). Similarly, women can also suffer from the repercussions of domestic violence, which is rarely studied but is of great importance in a close-knit society such as KSA. According to a United Nations (UN) report, every 4/10 women in Arab countries suffer from physical, sexual, or mental violence by their family members (Gosadi, 2019; Noor, 2019; Alluhidan et al., 2020). Therefore, it is necessary to study these social issues as well while addressing disability issues at the medical level in order to reduce the disability rate in the KSA society.

Disability assessment programs such as SNMHS

The literature review shows that the available literature provides only limited information on the actual prevalence rates of mental and physical disorders in KSA. This situation limits the government’s ability to develop a specific policy and plan for dealing with disabilities (Albejaidi and Nair, 2019; Alluhidan et al., 2020). For this reason, certain programs are being developed that aim to collect accurate data and better information on the prevalence of disabilities and their correlates. SNMHS is one such program that assesses mental disorders in the Saudi population (Alotaibi et al., 2022). It uses both high-quality standardization in theaters and field surveys to produce WHO-recommended survey analyses. The main objectives of the program are to assess mental disorders in the Saudi Arabian population, examine prevalent treatment patterns, and determine the social costs associated with these disorders with the overall goal of improving the quality of life (Alnahdi, 2020; Khasawneh and Alkhawaldeh, 2020; Alotaibi et al., 2022). These programs also address the social problems leading to mental disorders and aim to help social and health policy makers in Saudi Arabia to update facilities and improve health management.

Policy and legislative measures

Most of the resources come from the top authorities; hence, the legislative measures and policy making by the government authorities are of immense importance in addressing the problem of disability rate in KSA. To this end, the KSA government has passed some legislation in the past, such as the MHA, which focuses on the overall improvement and comprehensive care of people with mental disabilities (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Altwaijri et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). It also takes into account the protection of the rights of patients, their families, and caregivers as well as the simplification of guardianship issues and capacity-building measures. Such a policy also ensures the continuous implementation of health-related laws and legislation to provide the right mechanism for dealing with disability (Al Ammari et al., 2021; AlHadi and Alhuwaydi, 2021). This type of policy has enabled the KSA government to operate a parallel system of governance as in other countries in the world and under the influence of international organizations in the field of healthcare and human rights, of which the KSA area is generally a part (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Al Ammari et al., 2021; BinDhim et al., 2021).

Financial arrangements for disability management

An important part of any public or private institution is financial management, because everything is supported by solid human and financial sources. In the case of disability services, much of the funding goes toward the salaries of medical and paramedical staff, infrastructure development, academic and vocational training, and the provision of certain disability and administrative services to the affected population (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Muzafar and Jhanjhi, 2020). A separate part of the budget is earmarked for health management, of which a limited part is spent on disability management. Thanks to the financial support, the population now has free access to psychotropic medication as well as psychological and social services offered in the area of mental and physical healthcare (Muzafar and Jhanjhi, 2020; Rahman, 2020). Despite the allocated budget, the government needs to spend more money to strengthen healthcare in general and disability management in particular to overcome the disability rates prevalent in the study populations (Alluhidan et al., 2020). In addition, some government rules, regulations, and provisions allow the hiring and employment of people with mental or physical disability in the service sector, especially in social assistance programs. In addition to salaries, they also receive allowances for other benefits such as housing and transportation (Alluhidan et al., 2020; Rahman, 2020). Furthermore, insurance policies and disability coverage programs provide basic financial support for patients. These measures help people with physical and mental disabilities to become regular, better integrated members of the community (Gosadi, 2019; Alluhidan et al., 2020).

Implications of human rights policies

Human rights are an outrageous demand of most nations that count themselves among the world’s openly growing nations. Saudi Arabia, the leading economic power of the Arab world in particular and the world in general, is certainly subject to human rights actualization measures (Sheikh et al., 2019). For this reason, certain human rights committees and agencies are working at the national level and in cooperation with international agencies to promote the human rights of people with disabilities. This committee recruits mental and physical health experts, among others, who work to promote human rights while persistently criticizing any regulation that violates basic human rights and the specific rights of persons with disabilities (Sheikh et al., 2019; Johansson et al., 2021). Such agreements are important because people with any type of disability are often socially mistreated, stigmatized, labeled, neglected, and abused. They are also discriminated against in education, employment, the workplace, and elsewhere and therefore need special laws and regulations to develop as healthy members of society (Gosadi, 2019; Alnahdi, 2020; Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022).

The national and international human rights organizations and committees are striving to take certain measures such as raising awareness among the masses to avoid negative attitudes, giving more consideration to human rights in disability centers and mental health facilities, increasing physical and financial support for the mentally ill and their families, and turning toward internalization and acceptance by the community instead of long-term placement of such disabled people in health facilities (Alahmadi and El Keshky, 2019; Goggin et al., 2019; Khasawneh and Alkhawaldeh, 2020; Toquero, 2020). In addition, national spending on disability management should be increased, and policies, programs, and laws to promote the rights of persons with disabilities should be generally improved. In addition to the general committees and international agencies, there are sometimes special committees in each mental and physical health institution and hospital, which usually meet as needed when certain issues related to the rights of persons with disabilities arise to gather thoughts and develop strategies for lawful action (Jumreornvong et al., 2020; Meleo-Erwin et al., 2021). These committees also assist government agencies in monitoring, inspecting, and evaluating the quality of health service. Such a committee should be established in every private or public disability center to ensure that the human rights of persons with disabilities are respected (Fong, 2009; Gu, 2021; Meleo-Erwin et al., 2021; Pettersson et al., 2023).

The main mental health organization and services

In KSA, the MOH is the main authority for public health management. It works in collaboration with its attached agencies that are responsible for planning, implementing, monitoring, evaluating, and taking timely action to provide health services (Al-Subaie et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). The MOH has continuously improved in recent years and established several mental and physical health management facilities in the KSA. These facilities have specialized departments for the treatment of mental and physical impairments and provide inpatient, outpatient, and emergency services (Reid, 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021). In addition, they collaborate with academic and research institutions and general hospitals in the areas of research and administration (Jumreornvong et al., 2020; Ramsetty and Adams, 2020; Gu, 2021). The private sector hospitals, community hospitals, and PHCs also provide patient care. Considering this status, there is still room for new support centers, research facilities, and community health facilities to regulate the disability rates prevalent in KSA (Fong, 2009; Ng et al., 2009; Osman and Diah, 2017). In addition, infrastructure should be developed according to the needs of modern society, as well as equipment, transportation, inpatient beds, outpatient clinics, rehabilitation centers, and emergency services, along with quick decision-making and well-trained medical staff to ensure the best disability management as in the advanced societies of the world (Session, 2019; AlSadrani et al., 2020; Sarasola Sanchez-Serrano et al., 2020).

Policy recommendation by WHO

The WHO has recommended some provisions for the appropriate inclusion of people with disabilities in the disability centers. The 10 most important provisions of the WHO are explained below in a schematic representation (Fig. 1) to facilitate understanding and arouse the reader’s interest (World Health Organization, 2021). According to these recommendations, physicians and mental health and disability professionals must undergo extensive training and continuously learn clinical skills for the management of disability crises (World Health Organization, 2021; Putra et al., 2022). This allows them to apply their knowledge and skills in particular practices and areas of responsibility, such as referring to psychiatrists, prescribing psychotropic drugs, supervising disability facilities, recommending treatment with or without psychotropic drugs, and providing counseling services to patients as needed and appropriate (Alotaibi et al., 2021). These regulations ensure that the stigma of disability is reduced, the access to healthcare is improved, and the recovery from temporary disabilities is accelerated (Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2021).

Provision of mental hospitals and community-based and residential facilities

Apart from the regular disability facilities, outpatient, and inpatient services, certain other community-based faculties are being provided to the disability populations; these may include the mental health hospitals as elaborated before and the rented housing facilities along with the managing care staff and nurses to support both patient and medical staff (Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2021). In mental hospitals facilities such as managed care, innovative community services, freedom of choice for medical service, and flexible payment systems are provided. However, the preference leans towards renting temporary facilities, often acquired without synchronizing bed availability for patient admissions, which discourages their use and emphasizes outpatient services instead (Nair, 2019; Alotaibi et al., 2022). As per the regulations of most developed nations, KSA is also looking forward to establishing such healthcare facilities instead of looking to halfway housing and supportive housing services, independent housing, and stable services to improve the living standards of patients and staff (Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022).

This transformation is backed by the benefits of independent housing with better quality life and less psychopathology in patients as compared to the alternative situation. Besides these housing facilities, some community residential facilities are also operating in KSA where the average stay period is 60 days, and if long-term stays are needed then patients are sent to mental and physically handicapped centers under the ministry of social affairs (Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2021). Some arrangements have also been made for severe cases of illness and disability in terms of inpatient and outpatient settings: intensive home treatment, crisis intervention strategies and special outpatients’ services, and multi-systematic therapies (Alotaibi et al., 2021; Putra et al., 2022). These services have enabled better and more feasible alternative options to hospital-based disability management along with cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction (Al Awaji et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2021).

Forensic facilities

There are separate but interconnected forensic wards in the centers for the disabled and hospitals where there are facilities for drug addicts, alcoholics, destitute, and mentally handicapped persons. However, the length of stay of patients in these forensic units is limited, while it can be longer for some patients depending on their health conditions and medical recommendations (Gosadi, 2019; Alnahdi, 2020; Toquero, 2020). These forensic units also collaborate with criminal justice, juvenile justice, and rehabilitation centers to ensure continuity of care for disability. Safeguards in forensic units are not as strict as in European countries, but are based on therapeutic modalities and risk stratification to take immediate and appropriate action in high-risk patients (Fong, 2009; Toquero, 2020; Jaeger, 2022). Depending on their health status, patients are soon transferred to rehabilitation centers to achieve a better recovery, with only a limited number of individuals being placed in forensic facilities on a long-term basis, as the conditions in such facilities may worsen the patient’s condition (Ng et al., 2009; Ferreras et al., 2017). Instead, they should be transferred in a timely manner to more humane treatment facilities and community-based services where they can experience social integration (Harness, 2016).

Access to facilities, equity, and treatment options

As the percentage of admissions to community-based institutions for the disabled is not regulated and the number of unassisted and segregated patients is not documented, the question of equal treatment and access to facilities arises in KSA (Alotaibi et al., 2022). In addition, the most advanced facilities are located in the major cities, which limits access for the rural population, who generally suffer more from disabilities than the urban population. This hinders the development of more health services in rural areas (Velaga et al., 2012; Alotaibi et al., 2021). Some other barriers such as ethnic, religious, and language barriers are lower in KSA compared to developed countries. Therefore, the establishment of health centers in untouched areas is of utmost importance for the treatment of disabilities. In addition, treatment options in such facilities must be carefully regulated. For example, health workers must not prescribe psychotropic drugs, antipsychotics, or anxiolytics under any circumstances, but only on a doctor’s order in acute emergencies (Al Awaji et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022). Trained and licensed staff may only prescribe nonpsychotic medications in urgent cases with or without consultation with senior staff (Alotaibi et al., 2022).

Need to train special healthcare staff and allied workforce

The training of physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, and health practitioners in both community and private settings in KSA is increasingly becoming the focus of attention, as in the past practitioners without training and knowledge were confronted with sheer results (Nair, 2019; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Alotaibi et al., 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the continuous education, training, and coordination of staff in disability care. In addition, it is necessary to coordinate with researchers around the world to improve medical detection, diagnosis, and treatment options according to the requirements and updated versions of modern healthcare systems (Goggin et al., 2019; Alotaibi et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022). In addition to equitable human resource management in disability and health centers, it is also important that counselors have access to schools and educational institutions where psychosocial support can reduce stigma, labeling, juvenile crimes, and the proportion of offenders (Alahmadi and El Keshky, 2019; Rueda and Cerero, 2019; Alnahdi, 2020). In general, resource allocation and healthcare delivery should be improved across different segments of society to enable skill sharing, multitasking and task shifting, and rational resource sharing between healthcare providers and consumers across KSA (World Health Organization, 2021). This can be achieved by combining documented health measures, interactive academic details, criminal justice reviews and feedback, healthcare reminders, modern opinions, changing research paradigms, and consumer-mediated health interventions at the practical level of behavioral healthcare in KSA (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022; Putra et al., 2022).

Consumer advocacy, familial associations, and public awareness

Several consumer organizations with mental health and disability professionals and human rights advocates are serving KSA. In addition, there are also several family organizations that advocate for disability management in the region (Rahman and Al-Borie, 2021). These actions are helpful as more consumers should be involved in policy design and implementation, planning and legislative strategies, and funding resources as part of a community-based approach (Werner and Shpigelman, 2019; Alluhidan et al., 2020; Chadwick et al., 2022). This trend needs to be continuously expanded in order to regulate the healthcare system in KSA in the same way as in modern industrialized countries around the world. In addition, nongovernmental organizations should also be involved in this change of social services as they can provide housing and other support services for people with disabilities (Alluhidan et al., 2020; Chadwick et al., 2022).

Public education and community awareness

In terms of the most important and serious issue, community awareness and interaction with the public, promoting mental health literacy among the public is of great importance. Raising public awareness can lead to early detection, diagnosis, treatment support, and healthcare for people with disabilities (Harness, 2016). In addition, public awareness also enables the enclosure of these people into the general community, which can overcome the stigmatization of people with disabilities with the optimistic prospect of becoming a productive, special member (Goggin et al., 2019; AlSadrani et al., 2020). In communities such as KSA, which tend to be closed-minded, despite some improvements, it is necessary to quickly implement a culture in which there is a partnership between educators, researchers, administrators, policy makers, government officials, religious counselors, the criminal justice system, the media, and social activists to promote the cause at all possible levels of the community (Adam and Kreps, 2006; Ee Wong, 2012; Harness, 2016; Chadwick et al., 2022). In recent years, public awareness and education have improved through coordination between government agencies, private professional organizations, and international public health pioneers in KSA (Harness, 2016; Egard and Hansson, 2021). They are committed to raising awareness among the general public as well as teachers, managers, politicians, social workers, psychologists, medical staff, pharmacists, and drivers in the healthcare sector. In the long term, such measures will prove to be cost-effective health management in KSA (Alsufyani et al., 2020).

Quality control, research, and monitoring

The data are collected annually from all healthcare facilities in KSA for general administrative matters under various departments of the MOH (Alotaibi et al., 2022). These data contain comprehensive information on all rules and regulations for disability and general healthcare facilities. They also show the shortcomings of facilities and staff in various areas. However, some important data on patient profiles are sometimes missing, which may limit the ability to examine the links between causes and outcomes for patient health analysis (Alotaibi et al., 2021). However, annual reporting to the MOH is still a larger platform that can be utilized to set appropriate policies and righteous guidelines for the future direction of the healthcare system if the KSA healthcare system is well managed (Alotaibi et al., 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022). There is a need to link advanced information technology with the healthcare system to address the prevailing gaps in the Saudi healthcare system and enable informed decision-making and appropriate regulation of the prevalence of disability in the coming years (World Health Organization, 2021).

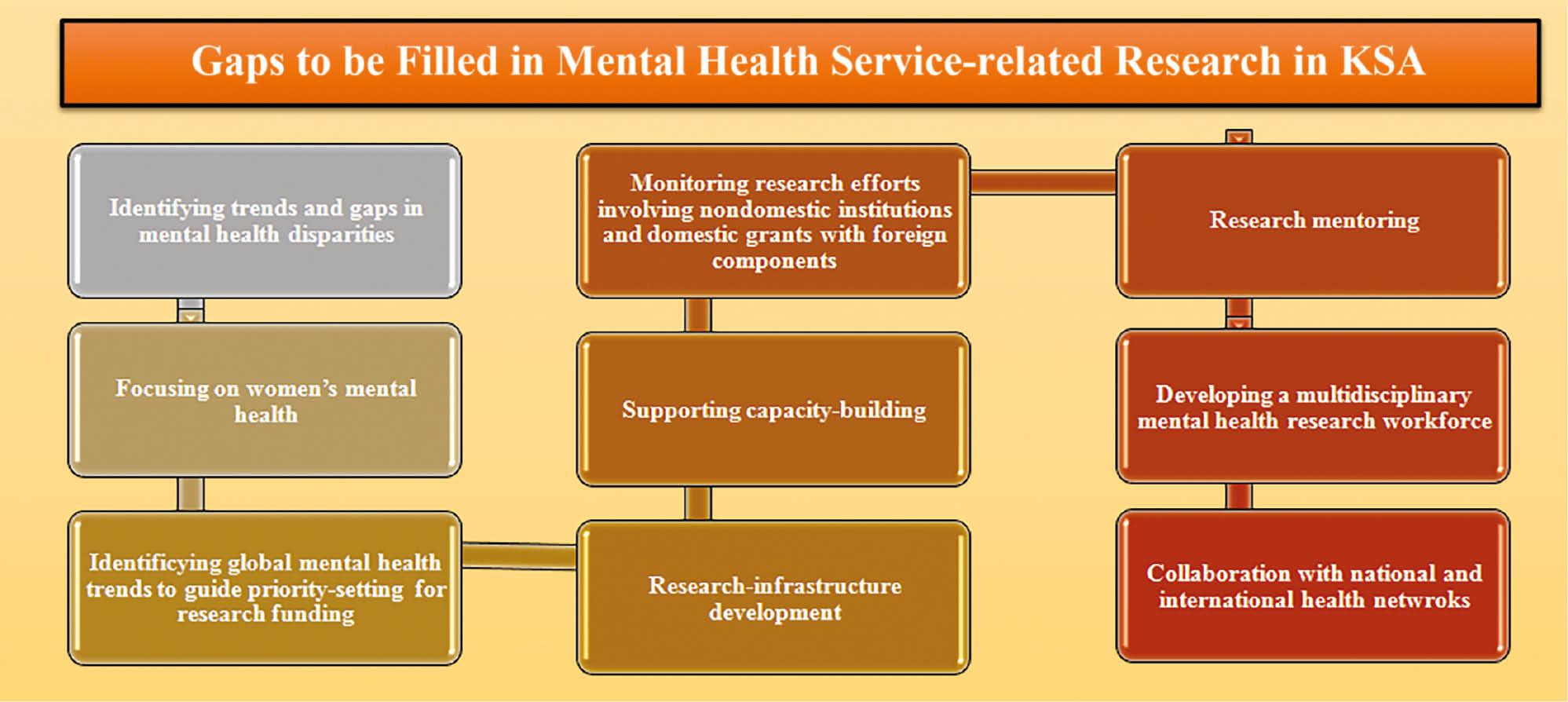

In addition, more emphasis should be placed on relevant research topics in academic research and funding should be allocated to disability research to support this ignored segment of society (Goggin et al., 2019; Toquero, 2020; Alotaibi et al., 2022). Although more resources and funding are being directed to this area over time, resulting in publications in high-impact journals, the gaps in psychiatric research need to be filled. Advances in this field are likely to lead to further developments and changes in treatment and disability strategies. To this end, it is necessary to focus attention on the research topics outlined in Figure 2.

The future directions

The future always holds hope, and after analyzing the current disability management, especially the mental health scenario in KSA, it is appropriate to develop appropriate disability management plans, policies, and programs (Hoq, 2020; Goggin et al., 2019; Toquero, 2020). Although the prevalence rates of disability are still lower compared to those of other countries, appropriate measures still need to be taken to limit or reduce the current suffering and deprivation. In academic education, it is important to integrate subjects related to disability management, mental health studies, and psychiatry for students, especially medical students (Macdonald and Clayton, 2013). The number of medical and psychiatric schools should be increased. The number of employed psychiatrists, residency programs, subspecialty programs, nurses, psychotherapists, psychologists, and trainers must also be increased (Macdonald and Clayton, 2013; Alsufyani et al., 2020; Marimuthu et al., 2022). It is important to stop the brain drain from the country. As the young population cannot find suitable programs in psychiatry, such as forensic, geriatric and liaison psychiatry, and others, students are opting for western education, and training at the national level should be improved in terms of teaching skills (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2019; Lebeničnik and Istenič Starčič, 2020; Sarasola Sanchez-Serrano et al., 2020; AlHadi and Alhuwaydi, 2021; Meleo-Erwin et al., 2021).

Research directives

Further detailed research is needed to identify the mentally and physically disabled people in KSA. The various dimensions for research should be the demographic interventions, sociological parameters, and behavioral characteristics that lead to disabilities among the people (Nair, 2019; Alotaibi et al., 2022). In addition, the natural causes for the development of disabilities need to be identified in order to develop an appropriate action plan to address this challenge. In addition, the cultural, social, and religious backgrounds should be investigated and the population should be educated on how to regulate their health or the health of those under their control. Better and more effective medications and treatments for such disabilities must be found, and the number of mental and physical healthcare centers, staff, and services must be increased (Alotaibi et al., 2021).

It is also important that scientists, educators, psychiatrists, psychologists, medical staff, nursing psychologists, and psychiatric social workers coordinate in the treatment of disabilities (Borgström et al., 2019; Goggin et al., 2019; Toquero, 2020). More care centers, rehab centers, and increased awareness are required among the general population to integrate into the community and reduce feelings of alienation among these people (World Health Organization, 2021). With the growing economy and greater openness of Saudi culture under Prince Muhammad Bin Salman, it is foreseeable that the development of medical research, environmental concerns, and social awareness among the general population in KSA will progress rapidly in the future (see Figure 3) (Alotaibi et al., 2021; World Health Organization, 2021; Alotaibi et al., 2022).

Recommendations and conclusion

Saudi Arabia is subject to constant change in the 21st century. Its healthcare system and the disability care sector have developed positively in terms of improving healthcare for the population. Government spending is increasing and the private sector is increasingly encouraged to spend more on consumer access to healthcare. Human rights bodies are being set up in healthcare facilities to regulate the rights of people with disabilities and to bring in foreign agencies for policy advice. Facilities and staff are gradually being increased, and systemic changes and corrections are being made in educational and research institutions. Despite all these measures, from the perspective of being the leading Arab country in the growing global economy, there is still a big gap that needs to be filled.

A more streamlined system is needed to integrate the effects of disabilities into society, with fair treatment conditions, insurance of patients’ rights, and financial support for financially constrained families. In addition, government spending on healthcare in general and on disability management in particular should be increased. Furthermore, the infrastructure in hospitals and care centers should be improved and more trained staff should be hired, as disabled patients are very sensitive and rely heavily on medical staff. The research paradigm should also shift to public health concerns to provide national guidance for policy changes, strategic program implementation, and comprehensive evaluation systems. In summary, there is still much room for changes and transformation in the healthcare system in KSA. However, there are optimistic prospects that future disability programs will be better managed, strategically designed, and result-oriented than the current ones and will contribute to the integration of disabled people into the community.